When teams experiment with messaging, the focus is usually on the words used. We debate phrasing, test benefits, tweak tone, and refine calls to action. All of this matters, but it often misses a quieter, more influential factor: the structure of the message.

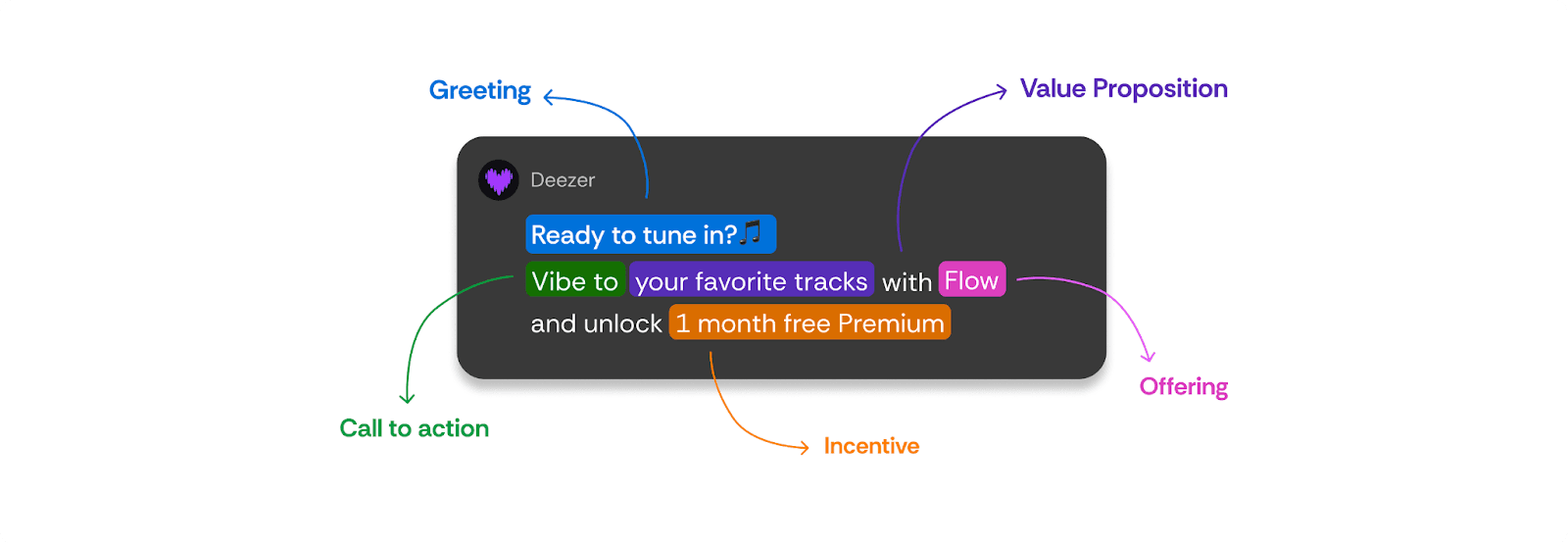

Message structure is the order in which ideas appear, which elements are included or excluded, and what the message chooses to emphasize first.

It’s easy to treat this as a formatting decision, but in reality, structure shapes how people interpret and respond to communication. Before a reader decides whether they like a message, they’ve already reacted to how it begins.

Every message structure is imbibed with an assumption about human behavior.

When a message opens with an incentive, it assumes motivation needs a push. When it opens with value, it assumes relevance comes first. When it’s short and direct, it assumes context is already understood.

Most teams test this once and apply them everywhere. The same structure gets reused across audiences, lifecycle stages, and contexts, often without being questioned.

Over time, this creates the impression that messaging has been “tested,” when in reality only the words have changed while the underlying structure stays fixed for everyone in their reachable audience.

Why there’s no single “best message”

Traditional content experimentation aims to find the single best-performing message and scale it. This works when audiences are uniform and intent is obvious. It breaks down as soon as users differ meaningfully in motivation, context, or decision-making style (which is usually the case - no two users are the same).

Different people respond to different kinds of communication.

Some want to understand the value before they care about the details. Others want to know exactly what’s being offered before deciding whether it’s relevant. Some respond to incentives immediately. Others tune them out entirely.

These differences aren’t just about taste. They reflect how people make decisions.

So the goal of varying message structure is not to pick one winning structure and send it to everyone. The goal is to make sure you have the best structure available for all kinds of users.

If you only ever send incentive-first messages, you’ll perform well with incentive-sensitive users and underperform with everyone else. If you only ever lead with value, you’ll do the opposite.

Optimizing for a single structure means implicitly choosing which users you serve well, and which ones you don’t. Reordering messages is how you avoid that tradeoff.

Vary structures without rewriting copy

Once you treat the parts of a message as distinct, structure becomes a variable you can explore. Crucially, this doesn’t require changing the content itself; only the order in which it appears.

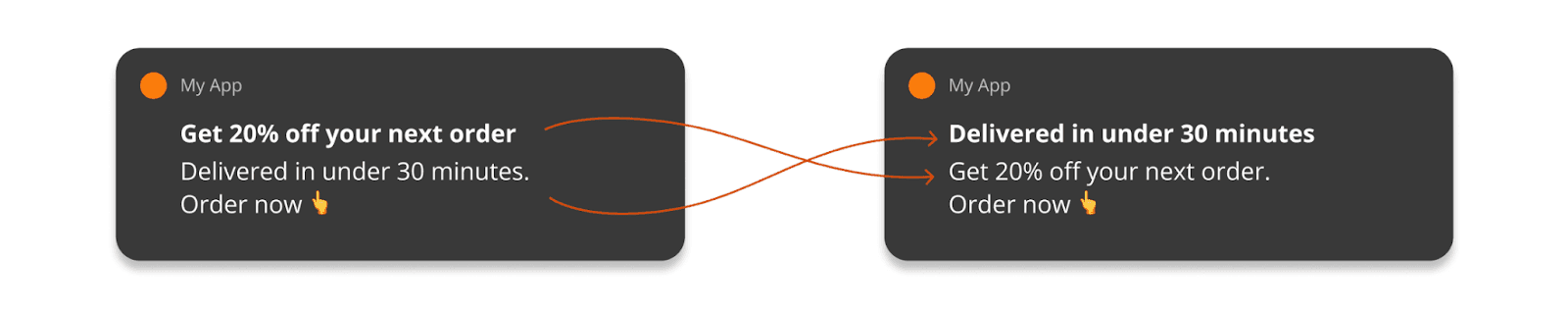

Consider the following two messages.

The words are identical. The incentive, the value, and the call to action are all the same. The only difference is order.

Yet these two messages test very different assumptions. The first assumes the incentive is what earns attention. The second assumes the inherent value of the experience should come first. This isn’t a matter of tone or persuasion. It’s a structural experiment that asks a clear question: Does this person respond when rewards are foregrounded, or when value is?

Over time, patterns start to emerge. These patterns are never constant, they evolve over time. And they describe how people prefer to be communicated with, not just which words they like.

Structure as a strategic lever

Experimenting with structure doesn’t require sophistication to begin. It can start by expressing the same message in a few different ways and paying attention to what’s emphasized first, rather than endlessly rewriting copy.

How this works in Aampe

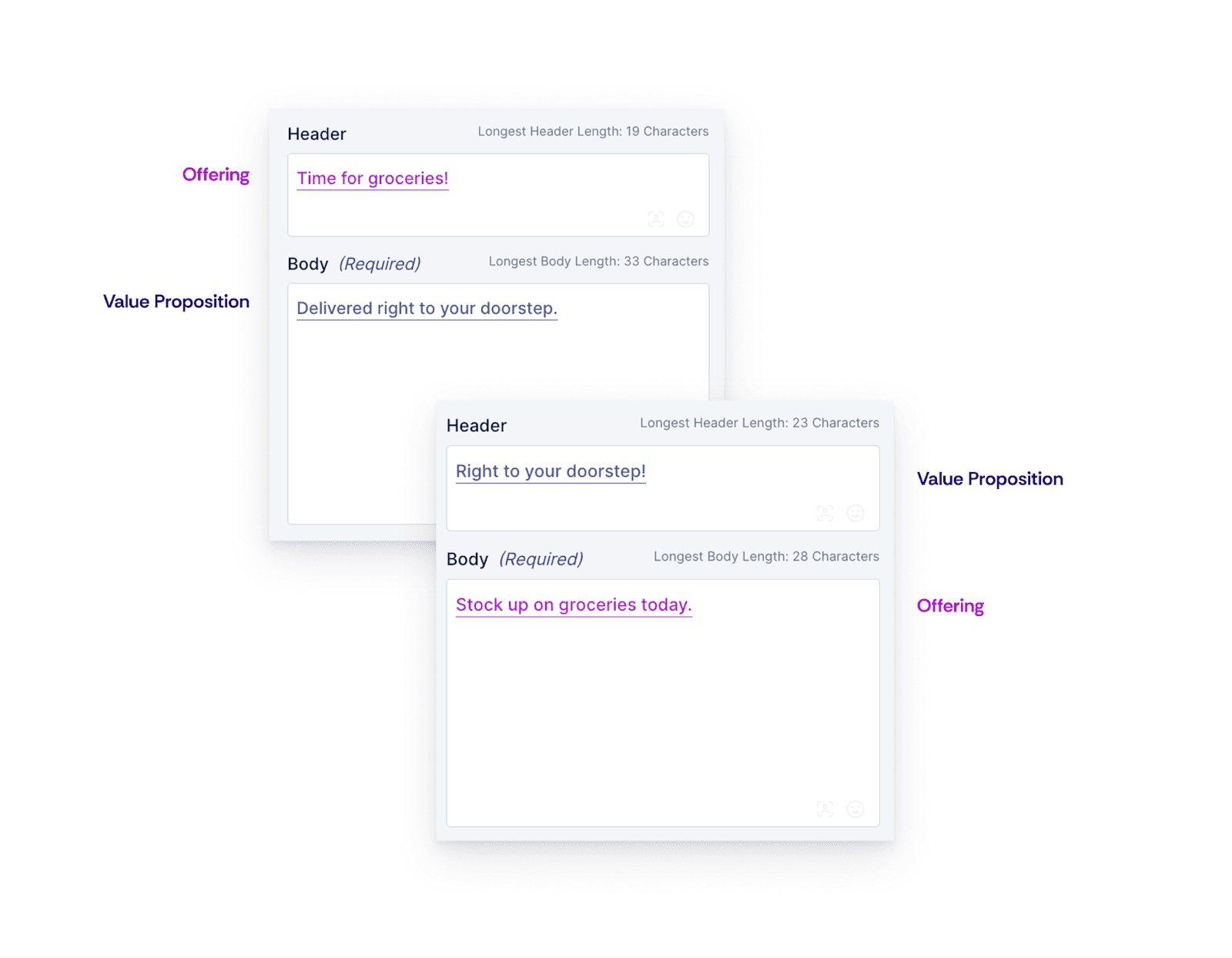

In Aampe, it’s very easy to do this. Create your first message, as you’d normally do. Once you’re done, just clone it, and repopulate the components in a different order.

Why variety helps agents—and users

AI Agents can only personalize effectively if they have meaningful choices. When your message library contains just one structure, agents are forced to reuse it for everyone, regardless of fit. But when you provide multiple valid structures for the same content, agents can learn which ones work for which users and adapt accordingly.

More structural variety means you’re implicitly catering to more user personas: deal-seekers, value-driven users, fast decision-makers, and cautious evaluators. Instead of optimizing for the “average” user, you give agents the flexibility to serve individuals in ways that feel natural to them.

The result is not just better performance, but better user experience. Messages feel less repetitive, less pushy, and more relevant and timely for every individual user.